Karl Tunberg's Writing of the Screenplay for Ben Hur

The screenplay which lies at the heart of the 1959 movie Ben-Hur was the product of a complicated evolution involving years of rewrites, changes and disputes. These changes and disputes gave rise to a very public and bitter controversy over screen writing credit. Indeed, this controversy is most likely the reason for the fact that out of the twelve categories in which Ben-Hur was nominated for Academy Awards, the only category in which the award was not actually given was for “Best Screenplay”.

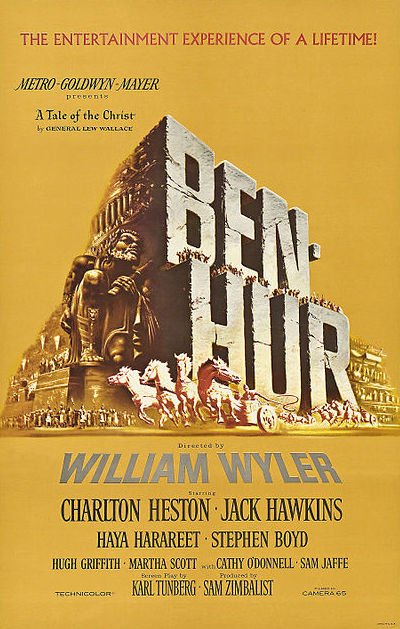

From the release of the film up to the second decade of the twenty-first century the dominant point of view represented in the large literature pertaining to this controversy has been that of the film’s director, William Wyler. The views of Charlton Heston, who mostly took Wyler’s side, have played a role too, though to a lesser extent than those of Wyler. Since the 1990s another voice has come to the fore – that of the novelist Gore Vidal, who worked on the script of Ben-Hur for a short period. The views of Sam Zimbalist, the MGM producer, who had instigated the remake of Ben-Hur in the mid-1950s, have been filtered through the various perspectives of Wyler, Heston, and Vidal, since Zimbalist had suddenly died in mid-production and before the public controversy over screenwriting credit. Once that controversy had emerged, Wyler and Heston, of course, presented Zimbalist’s views as entirely congruent with their own – as did Gore Vidal in a later period.

The statements of Wyler and/or Vidal (and their accounts are not always in full agreement) permeate not only the scholarly material and the formally published printed books relating to the 1959 Ben-Hur movie, but also much of the material on the subject available on the internet, such as the inaccurate account of the screenwriting for the 1959 Ben-Hur movie currently (in early 2023) posted on Wikipedia, or some of the incredibly misinformed statements about the writing of the movie to be found among the “Trivia” on IMDb (Internet Movie Database).

But the year 2016 saw the publication by Edinburgh University Press of “Ben-Hur: The Original Blockbuster”, written by Jon Solomon. Included in this massive 928-page study of the entire literary and dramatic phenomenon that descended from the nineteenth-century novel Ben-Hur (by Lewis Wallace) is a detailed account of the development of the script on which the 1959 movie was based. Solomon, unlike any scholar who had written previously about Ben-Hur, offers a careful analysis and comparison of the different drafts of this screenplay and the contributions of each writer (where it is possible to determine this). Solomon’s masterful study decisively corrects most of the misconceptions that had arisen about the 1959 movie’s screenplay during the intervening decades. The observations we offer here are merely supplemental to Solomon’s work.

It was Sam Zimbalist who originally chose Karl Tunberg as the writer for the project to remake Ben-Hur. He did so after after having worked with Karl on Beau Brummell (released in 1954). Although Karl had a special inclination towards comedy and had built most of his earlier reputation on comedies, Beau Brummell showed he could also write historical epics. And right after Beau Brummell, Tunberg had scripted The Scarlet Coat, another large historical drama. Did Zimbalist already have a script for Ben-Hur, which he asked Karl Tunberg to rewrite? Or did he simply ask him to undertake a new adaptation of Lew Wallace’s novel Ben-Hur? All evidence known to us indicates that Karl Tunberg wrote a new script from scratch, and we can add that earliest scripts preserved in the Margaret Herrick Library of the The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences bear Karl Tunberg’s name. In any case, there is no doubt that the script completed by Tunberg departed vastly from the novel (see, for example, the discussion by Morsberger and Morsberger, Lew Wallace, p. 482). Tunberg delivered his script to Zimbalist quite some time before Wyler had any connection with the project. In fact, MGM shelved the Ben-Hur project, not because anyone at that point objected to the script, but because the studio was in financial trouble, and everyone could see that it would cost a lot of money to make Ben-Hur. But the Ben-Hur project was finally revived by Zimbalist, who managed to convince MGM that it was worth the financial risk. He was prepared to bet that the revenues generated by Ben-Hur could solve MGM’s financial problems. The majority of published sources indicate that Zimbalist was dissatisfied with the script even at this stage and brought in writers (notably Maxwell Anderson and S. N. Behrman) to revise it (see, just for example, the discussions by Madsen, pp. 341-342; Heston, In the Arena, p.186; Miller pp. 360-361; Herman, 394; Kaplan, p. 440).

Karl Tunberg, however, always asserted that Zimbalist’s readiness for changes in the script came after Wyler was induced to take on the project. A memo from Zimbalist (now in the Margaret Herrick Library collection: MHL,Turner/MGM Scripts, 278-f. B-944) dated 14 March 1957 reveals Wyler already at work on the project and conducting a screen test for Cesare Danova (even though Wyler did not sign a contract until September). But the earliest indications we have found for the involvement of Anderson or Behrman date from the second half of that year (these include versions of screenplays and notes). Before Wyler joined the project Zimbalist seems to have been sufficiently contented with the script to show it to the prestigious directors he wanted to attract to the project. In fact, the only major dispute between Karl Tunberg and Sam Zimbalist pertained not to the script, but to the director. Karl openly favored Sidney Franklin, and was never enthusiastic about Wyler. In the early stages of the project’s development Franklin, working with Karl Tunberg and Sam Zimbalist, put a lot of time into planning his approach to scene structure and emphasis, and submitted these plans in the form of a 200 page outline (material dating from 15 December 1954 to 3 August 1955: MHL,Turner/MGM Scripts, 274-f. B-919). But Zimbalist, when the Ben-Hur project was revived again by MGM after a period of shut-down, was by this time advocating William Wyler on the basis of Wyler’s very high reputation, and the very young Wyler’s involvement with the 1926 silent film Ben-Hur. Franklin morever became ill; so Karl reluctantly yielded to Zimbalist’s preference for Wyler.

When Wyler read the script, he hated it and demanded changes. Most sources agree that he particularly objected to its “modernist” dialogue (although Jan Herman [A Talent for Trouble, p. 394] makes all aspects of the script, including its conception and characterization, equally the objects of Wyler’s aversion). Wyler wanted dialogue that sounded slightly archaic, which he thought would evoke a distant period in the past. Tunberg believed that, because the language people spoke 2000 years earlier sounded contemporary to them, the modern audience should relate to it as contemporaries would have done – since the film in any case would necessarily be made in a modern language, not an ancient one. This was a legitimate philosophical difference, and Karl Tunberg would never have claimed that his dialogue had any sort of archaic flavor. Zimbalist, anxious to bring the huge project to fruition, and equally anxious to have Wyler direct the film (and to this end he had persuaded MGM to offer Wyler an unprecedented salary), was ready to comply. By this time Karl Tunberg was already embarking on another film project, Count Your Blessings, for which he was not only the screenwriter, but also the producer. It is easy to suspect – though we have found no concrete evidence for this – that Zimbalist expedited Karl’s assignment to a new project on which he would also be producer (a role which Karl at this stage of his life wanted to play more often, together with being writer) so that Wyler could have a free hand to adapt the Ben-Hur script to his liking, unhampered by resistance from Karl Tunberg, a resistance that would have been inevitable had Karl been on the Ben-Hur set while the film was being shot in Italy. In any case, Karl trusted Zimbalist, with whom he was on very good terms, to prevent radical changes to the script.

It was at this point that S. N. Behrman and Maxwell Anderson were brought into the project. Notes by Behrman on previous versions of the script, along with comments by Zimbalist, dating from December 1957 are preserved in the Margaret Herrick Library collection (MHL, Turner/MGM scripts, 281-f. B-962). In the same collection are several drafts of the script dating from late 1957 or early 1958 that include, in addition to Karl Tunberg’s name, the names of either Behrman or Anderson (MHL, Andrew Marton Papers, 2-f. 19; MHL, Turner/MGM scripts, 280-f. B-954; 280-f. B-955; 281-f. B-963; 282-f. B-964; 282-f. B-965).There are also revisions by Karl Tunberg alone dating from early 1958 (MHL,Turner/MGM scripts, 282-f. B-971; 283-f. B-972; 283-f. B-973). Changes in the structure of the script seem to have been quite small. It is very difficult to isolate which revisions come from Behrman or Anderson, but probably they contributed – in response to earlier criticisms of ‘modernist’ dialogue – a more archaic-sounding diction. Indeed, Charlton Heston reports that by the time he, with Wyler’s approval, was hired to play the part of Ben-Hur, the language seemed to be excessively “medieval” (Heston, In the Arena, p. 186).

Wyler is said not to have read the revised script until early in 1958. He apparently did so when he was actually on the plane to Italy to begin work on making the film. He rejected this version of the script too, but (if we believe the statements of Heston) he did so for reasons more or less opposite to those which had caused him to dislike the earlier version of the screenplay. Now the dialogue was too archaic. Zimbalist is said to have agreed. More rewriting was needed – and quickly. At this point Gore Vidal was brought onto the project. There is disagreement in many of the secondary sources as to whether he was hired before Christopher Fry, or at the same time. But the correspondence of Wyler himself kept in the Margaret Herrick Library collection resolves the issue. Vidal worked as a writer on the set from 23 April 1958 to 24 June 1958; but Fry was on the set from 29 April 1958 to 19 January 1959 (MHL, William Wyler Papers, 2-f.21). Vidal had been asked somewhat earlier by Wyler (perhaps in late 1957?) to participate in Ben-Hur, but had refused. In 1958, however, Vidal changed his mind, and he started working with Wyler on the set in Italy to revise the screenplay’s dialogue.

Gore Vidal’s role in the revising of the screenplay of Ben-Hur came under the spotlight in the 1990s as a result of several documentaries and articles in newspapers and magazines. Controversy arose when Vidal, who by the 1990s was interested in publicizing how gay men had managed to survive in the artistic world of the 1950s (a period, of course, when gay people in all walks of life were subject to incredibly unfair discrimination), claimed to have rewritten a crucial scene featuring Ben-Hur and Messala to include subtle hints of a homosexual relationship between them. Moreover, as Vidal tells it in the Celluloid Closet (1996) and elsewhere, he had discussed this approach to the scene beforehand with Wyler, who had not rejected the idea outright, but warned him to keep it toned down.

In fact, the claims about Vidal’s participation seem to have grown over time. In Axel Madsen’s 1973 biography of Wyler, the so-called “authorized” biography, Vidal’s role is not even mentioned. But in the biographies of Wyler by Jan Herman (1995) and Gabriel Miller (2013) Vidal’s account is reported, though both authors agree that Wyler himself in later years had no recollection of a conversation with Vidal about the Ben-Hur and Messala scenes. Vidal, moreover, asserted in the 1990s that he substantially rewrote the first half of the screenplay, and in more than one source he is stated to have changed the presentation of the reunion of Ben-Hur and Messala from one scene into two. Indeed, in the well-respected documentary entitled Ben-Hur: The Making of an Epic, narrated by Christopher Plummer, Gore Vidal is styled as “author” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ChPXI1gJ-yo). The presentation of Gore Vidal as a major (or the major) contributor to the Ben-Hur screenplay is echoed in all the main biographies of Vidal, and is reinforced by an article by film historian F. X. Feeney (“Ben-Gore: Romancing the Word with Gore Vidal”), who argues, after examining “the shooting script” saved in the library of the Motion Picture Academy (Margaret Herrick?), that the whole conception of scenes in which Ben-Hur and Messala face each other individually, and especially the reunion scene in involving the throwing of javelins (which takes place before the two are alienated), is that of Vidal.

We have examined in the Margaret Herrick library multiple copies of the Ben-Hur script in various stages of revision, and it is difficult to isolate one single “shooting script”. All the scripts are dated. All, except for one folder, bear the name of Karl Tunberg, and in a few drafts of late 1957 and early 1958 the names of Behrman or Anderson are added to that of Tunberg (see above). Vidal’s name is absent (as is that of Fry). The copy which lacks specific indication of author is an incomplete script (MHL, Charlton Heston Papers, 5-f.49) containing 160 pages of changes made from 30 June 1958 (after Vidal had left the project) to 26 June 1959. Much of the material in this folder is identical to the rewrites made by Tunberg himself in the final stages (see below). There is no doubt that Feeney had immersed himself in the works of Vidal before studying the script (or scripts?), but his assertion of Vidal’s conception and authorship of scenes dramatizing the relationship between Messala and Ben-Hur (in the form they were shot) is hard to verify. We should point out that the reunion scene between Messala and Ben-Hur involving javelin throwing is already present in early versions of the script produced long before 1958. Moreover, the whole conception of the relationship between Messala and Ben-Hur (without the homo-erotic overtones which Vidal undoubtedly did see in this scene, when he worked on the set) is actually typical of Tunberg. This subplot and basic conflict – a deep friendship between two leading male characters that is compromised by political factors – is employed by Karl Tunberg in other films: consider the relationship between Brummell and the prince-regent in Beau Brummell, or the relationship between Ferris and Ng in The Seventh Dawn. Charlton Heston, who was a partisan of William Wyler during much of the stormy process of making Ben-Hur, asserts that Vidal rewrote an early scene between Ben-Hur and Messala, but insists that it was clear to everyone, after one rehearsal of this scene, that the scene had to be re-done, and Vidal was off the film. Heston also recalls (correctly) that Vidal was on the film for a very short time, and he characterizes Vidal’s claim that he substantially rewrote the first half of the script as “incredible” (Heston, In the Arena, p. 187). It is worthwhile here to quote the words of Jon Solomon. “Vidal’s retrospective claims in the media that Tunberg’s script was ‘awful’ or that the first third had to be completely rewritten ignore the degree to which the finished product reflected Tunberg’s earliest screen adaptations of the novel and speak more to the polished quality of the release version of the film and Vidal’s own self-promotion. Wyler’s later statement that Tunberg had written only the three words ‘The Chariot Race’ without any further details were also utterly inaccurate. In addition to the 1955 and 1957 Canutt ‘action breakdowns,’ Tunberg’s 218-page script contains more than twenty-five pages describing the race” (Solomon, Ben-Hur, p. 742).

When Vidal left the project in late June 1958, the only writer left to work on the set was Christopher Fry. Heston, in his autobiography, is almost effusive in his praise of Fry’s rewriting of the screenplay’s dialogue. Much of this work consisted of retaining a slightly archaic quality to the diction, while retreating from the excessive and stilted archaism which had infiltrated earlier attempts to revise the “modernist” dialogue. An example quoted in numerous sources was Fry’s changing of the too “modern” (from the viewpoint of Wyler and Heston) “How was your dinner” into “Was the food not to your liking” (one of the few dialogue changes which actually remained in the final drafts of the script). There is consensus among Wyler’s biographers that Wyler admitted Fry’s changes were not extensive in quantity. Heston agrees, adding that Fry’s changes were seldom structural, but nearly always linguistic.

A major force which had restrained and controlled the considerable antagonisms among the leading figures in the Ben-Hur project was suddenly removed in November 1958, when Sam Zimbalist died of a heart attack in Italy while overseeing the film’s production. We should note in passing that the relationship between Wyler and Zimbalist in all the biographies of Wyler and Vidal, as well as in Heston’s autobiography, appears to be one of consensus and concord. But it will not be out of places to note a surviving letter from J. J. Cohn to Zimbalist’s widow dated 28 November 1958, which also hints a difficult relationship between Zimbalist and Wyler during the actual shooting of the film (MHL, Sam and Mary Zimbalist Papers,1-f.9). Be this as it may, with Zimbalist gone, preliminary shooting on Ben-Hur finished with Wyler in command.

In 1959 Karl Tunberg was still involved with the production of Count Your Blessings. By the early part of this year, Tunberg was back in Los Angeles and, along with other MGM executives and Wyler himself, he viewed screenings of rough cuts of Ben-Hur. There was agreement among all parties concerned that many of the scenes – and these mainly comprised the scenes which had been reworked by Fry and others – were unsatisfactory. The need for re-working had been clear to MGM executives from the beginning of that year, and perhaps even earlier -- as is indicated by a letter from J. J. Cohn to Zimbalist’s widow dated 13 January 1959 (MHL, Sam and Mary Zimbalist Papers,1-f.9).

Karl Tunberg had been off the Ben-Hur project from 5 May 1958 to 14 April 1959 (dates are specified a letter of 6 July 1959: MHL,William Wyler Papers, 2-f.21), but he had continued, at Zimbalist’s request, to contribute material to Ben-Hur (for more on this, see below). Now he agreed to rewrite Wyler’s changed material and to compose some added scenes, all of which went into the final version of Ben-Hur – something which is clearly confirmed in the Writers Guild’s position statement made after arbitration. These changes and restorations, however, receive no mention in most of the literature published since the release of Ben-Hur about the controversies over authorship of the screenplay.

Wyler, supported by Heston, still wanted Fry to get co-credit for the screenplay because of the work Fry had done while on the set. For a brief period in 1959 Karl Tunberg, whose first impulse was usually to avoid conflicts, seems to have been willing to compromise with Wyler and to accept joint credit (this is suggested by a letter of Wyler dated 8 July 1959: MHL, William Wyler Papers, 2-f.21). But Karl soon changed his mind, either because the Writers’ Guild officials, who were very sensitive in this period about their recently won rights to determine and protect writers’ credits, urged him not to yield, or because he decided himself that agreeing to a joint credit for Ben-Hur was unfair.

Karl himself never talked about his momentary readiness to yield, and in any case his resolve must have been strengthened when the Writers Guild initially investigated the claim and pointed out that the contributions of Fry which had survived in the final version of the screenplay were not nearly enough to warrant co-credit. Guild rules required a minimum of 25% of a finished product to be the work of a writer entitled to co-credit. But Wyler was determined to press his case, and the matter was submitted to a formal arbitration of the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild’s arbitration board (consisting of experienced writers, each working without knowledge of the others) unanimously awarded full and sole credit for the script to Karl Tunberg. Wyler appealed the decision – offering to submit new material. After hearing the appeal, and inspecting the “new” material, the Guild reiterated its arbitration decision: the final product was overwhelmingly the work of Karl Tunberg, and he must be awarded sole screenwriting credit. When Christopher Fry learned of the Guild’s arbitration, he indicated that he was prepared to accept it.

Wyler reacted by launching a publicity campaign against Tunberg, implying that the Guild’s decision was biased and corrupt, since Tunberg had been a past president of the Guild. Wyler, moreover, enlisted help from every quarter in his wide circle of Hollywood contacts. Among the material Wyler left to Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (currently in the Margaret Herrick Library) one can even find a letter to the Guild written by Sam Zimbalist’s widow dated 2 November 1959, in which she urges the Guild to reconsider and suggests that her late husband would have favored a shared credit (MHL, William Wyler Papers, 2-f.21). While this letter may have been a spontaneous expression from Ms. Zimbalist, we wonder what role J. J. Cohn, a good friend of Wyler, who had befriended Ms. Zimbalist since her husband’s death (a considerable part of their voluminous correspondence is available in the Herrick Library) could have had in soliciting this letter.

In response to this pressure, the Guild published a formal statement, which reiterated the method and results of the arbitration itself, and which accused Wyler of attempting to undermine the unbiased nature of the arbitration process. We reproduce here the full statement of the Guild, published in the Hollywood Reporter, on Friday, November 20, 1959 (p. 5).

On 24 November 1959 Wyler published in Hollywood Variety a response to the Guild’s statement published four days earlier. While accepting the Guild’s first ruling that Tunberg was the only writer who had written a complete screenplay for the 1959 version of Ben-Hur, Wyler rejected the second and third rulings. In other words, Wyler denied that Tunberg had continued throughout the filming to contribute material that remained in the final product (ruling 2), and that Tunberg alone had done the rewrites needed for the final four months of retakes (ruling 3). This response by Wyler is surprising because it is so much at odds with other evidence. Perhaps in anger and in the heat of the controversy, Wyler had actually forgotten some of the details of recent events. Whatever the explanation, in Wyler’s own correspondence there is clear allusion to the fact that Tunberg even while “off assignment” in late 1958 had been called upon to contribute script material (MHL, Sam and Mary Zimbalist Papers, 1-f.5; William Wyler Papers, 2-f.21)! Moreover there are five different sets of retakes still saved in the Herrick Library dating from April to July 1959. Each of them consists of very extensive handwritten rewrites on a section of script, and a fair copy which incorporates these handwritten changes into a clean copy of revised script. The handwriting is exclusively that of Karl Tunberg, and Karl Tunberg is the only authorial name specified on each of these sets of rewrites (MHL,Turner/MGM scripts, 286-f.B-1004; 286-f.B-1005; 286-f.B-1006; 286-f.B-1007; 286-f.B-1008). A collection of retakes left to the same library by William Wyler contains suggestions by Wyler, but virtually no other retake material (MHL, William Wyler Papers, 2-f.17; 3-f.33). Karl Tunberg commented on all of this in an interview published by the San Diego Union in 1960, and Jon Solomon’s assessment of this interview is worth quoting here. “His <Tunberg’s> opening salvo … accused Wyler of having a Napoleonic complex, evident in the ubiquitous presence of his name in most of the Ben-Hur advertising, and not tolerating solo credit for anyone else. He followed with a sober review of the project’s history – new to the audience – from 1953 as a proposal designed to counter the incursions of television, his second draft approved by Zimbalist and Schary, the work with Franklin, the dormant period of turmoil in the studio leading to the presidency of Vogel, and then the production under Wyler from 1957. He explained the Guild’s procedures, and after confirming that Fry did not pursue any appeal, he concluded with an accurate and sarcastic anecdote: ‘Wyler said Fry’s contributions were intangible, scribbled on the backs of envelopes and memo pads, which brought the rejoinder from writer Daniel Taradash, “Why not give director’s credit?”’ Tunberg concluded by saying, again accurately, that Fry’s contributions submitted to the arbitration committee by MGM amounted to no more than about eleven pages of his 200-plus-page script” (Solomon, Ben-Hur, pp. 785-786).

Wyler’s campaign, however, had its effect. As mentioned at the beginning of our narrative – “Best Screenplay” was the only category in which Ben-Hur was nominated for an Academy Award, but did not receive it. And when Heston received his Academy Award for “Best Leading Actor”, he made a point of publicly thanking Christopher Fry for Fry’s work on the script. Heston’s speech provoked the Screen Writers Guild to send Heston a letter accusing him of ignoring the Guild’s fair process and trying to denigrate Tunberg’s reputation. But the damage had been done.

Was the Guild’s arbitration corrupt, as Wyler and Heston (and later Vidal) implied, and influenced by the fact that Karl Tunberg some years earlier had been a Guild president? Such an assumption would require us to ignore the anonymous nature of the arbitration process itself, and to pay no attention to the fact that people involved in movie production in Hollywood in the late 1950s, including many or most of the screenwriters, would have been much more intimidated by powerhouses like Wyler than by a former president of the Screen Writers Guild, as the Academy Awards of that year showed! The script for Ben-Hur may indeed not have pleased all the people involved in the project all of the time, but the Screen Writers Guild’s investigation and arbitration clearly offers us the best final judgement. The final script for Ben-Hur – the script that was actually represented in the epic film that was released in theaters – was overwhelmingly the work of Karl Tunberg.

Selected Bibliography

Belton, John. American Cinema/American Culture. New York: 2008.

"Ben-Hur Rides a Chariot Again." Life. January 19, 1959.

Canutt, Yakima and Drake, Oliver. Stunt Man: The Autobiography of Yakima Canutt. Reprint ed. Norman, Okla.: 1997

Cole, Clayton. "Fry, Wyler, and the Row Over Ben-Hur in Hollywood." Films and Filming. March 1959.

Coughlan, Robert. "Lew Wallace Got Ben-Hur Going—and He's Never Stopped." Life. November 16, 1959.

Cyrino, Monica Silveira. Big Screen Rome. Malden, Mass.: 2005.

Dowdy, Andrew. The Films of the Fifties: The American State of Mind. New York: 1973.

Eagan, Daniel. America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: 2010.

Eldridge, David. Hollywood's History Films. London: 2006.

Feeney, F.X. "Ben-Gore: Romancing the Word With Gore Vidal." Written By. December 1997-January 1998.

Hall, Sheldon and Neale, Stephen. Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Detroit, Mich.: 2010.

Herman, Jan. A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood's Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler. New York: 1997.

Heston, Charlton. In the Arena. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Hezser, Catherine. "Ben Hur and Ancient Jewish Slavery." In A Wandering Galilean: Essays in Honour of Sean Freyne. Boston: 2008.

Joshel, Sandra R.; Malamud, Margaret; and McGuire, Donald T. Imperial Projections: Ancient Rome in Modern Popular Culture. Baltimore, Md.: 2005.

Kaplan, Fred. Gore Vidal: A Biography. New York: 1999.

Kinn, Gail and Piazza, Jim. The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History. Rev. and updated edition. New York: 2005.

Madsen, Axel. William Wyler: The Authorized Biography. New York: 1973.

Malone, Aubrey. Sacred Profanity: Spirituality at the Movies. Santa Barbara, Calif.: 2010.

Miller, Gabriel, William Wyler. The Life and Films of Hollywood’s Most Celebrated Director. Lexington, KY.: 2013.

Morsberger, Robert Eustis and Morsberger, Katharine M. Lew Wallace, Militant Romantic. New York:1980.

Parish, James Robert; Mank, Gregory W.; and Picchiarini, Richard. The Best of MGM: The Golden Years (1928-59). Westport, Conn.: 1981.

Pomerance, Murray. "Introduction." In American Cinema of the 1950s: Themes and Variations. New Brunswick, N.J: 2005.

Raymond, Emilie. From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics. Lexington, Ky.: 2006.

Sennett, Ted. Great Movie Directors. New York: Abrams, 1986.

Solomon, Jon. Ben-Hur: The Original Blockbuster. Edinburgh: 2016.

Solomon, Jon. The Ancient World in the Cinema. New Haven, Conn.: 2001.

Steinberg, Cobbett. Film Facts. New York: 1980.

Stempel, Tom. American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing. Lexington, Ky.:2001.

The Story of the Making of 'Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ'. New York: 1959.

Thomas, Gordon. "Getting It Right the Second Time: Adapting Ben-Hur for the Screen." Bright Lights Film Journal. May 2006.

Vidal, Gore. "How I Survived the Fifties." The New Yorker, October 2, 1995.

Winkler, Martin M. Classical Myth & Culture in the Cinema. New York: 2001.

Wyler, William. "William Wyler." In Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood's Golden Age at the American Film Institute. George Stevens, Jr., ed. New York: 2007.